Three Major Categories of DBMSs

- Online transaction processing (OLTP)

- Handle a large number of user-facing requests and transactions that are often predefined and short-lived

- Online analytical processing (OLAP)

- Handle complex aggregations

- OLAP databases are often used for analytics and data warehousing and are capable of handling complex, long-running ad hoc queries

- Hybrid transactional and analytical processing (HTAP)

- These databases combine the properties of both OLTP and the OLAP stores

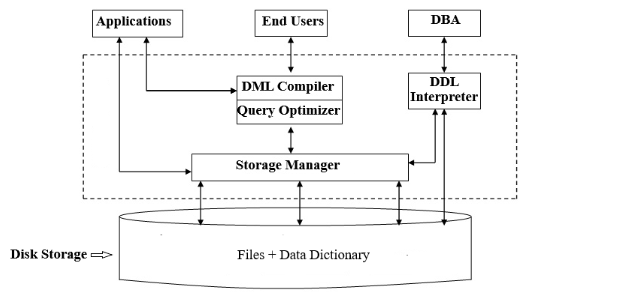

DBMS Architecture

Database Management Systems use a server model in which database system instances serve as servers, and application instances act as clients. From there, client requests arrive via a transport subsystem as queries.

Upon receipt, the transport subsystem hands the query to the query processor, which parses, interprets, and validates it. Some RBAC/access control checks are performed after the query is interpreted.

The parsed query is passed to the query optimizer, which eliminates redundant/impossible parts of the query and finds the most efficient way to execute it based on internal statistics and data placement.

From there, the query optimizer produces a query that is almost like an execution plan for the steps required to retrieve the data. This portion is handled by the execution engine, which collects the results of local and remote operations.

Local queries are executed by the storage engine. The storage engine has several components with dedicated responsibilities:

- Transaction Manager

- Schedules transactions and ensures they cannot leave the database in a logically inconsistent state.

- Lock Manager

- locks on the database objects for the running transactions, ensuring that concurrent operations do not violate data integrity.

- Access Methods

- Buffer Manager

- Caches data pages in memory

- Recovery Manager

- Maintains the operation log and restores the system in the case of failure

Memory vs. Disk-Based DBMS

DBMSs store data in both memory and on disk, but they differ in which medium is the primary source of truth.

Disk-Based DBMSs

- Store most data on disk; use memory mainly for caching and temporary working space

- Require careful handling of:

- data references (page/record identifiers rather than direct pointers)

- serialization formats (converting in-memory objects ↔ disk representation)

- freed space and fragmentation (reusing space efficiently over time)

- Use specialized on-disk data structures (e.g., disk-friendly tree/index layouts) to minimize expensive disk I/O

In-Memory DBMSs

- Store most data in RAM; use disk primarily for recovery and logging

- Benefits:

- Much faster reads/writes due to direct memory access vs. disk I/O

- Easier manipulation of dynamically allocated data structures in memory

- Avoids many disk-allocation concerns (the system manages memory allocation rather than you managing disk pages directly)

- Tradeoffs:

- RAM is volatile → crashes, bugs, or hardware failures can cause data loss without durability mechanisms

- Typically more expensive and often harder to scale economically than disk-heavy systems

Durability in In-Memory Stores

- To reduce data loss risk, in-memory systems commonly:

- write updates in batches to a large sequential log (fast to append)

- recover by replaying the log to reconstruct the latest database state

Column- Versus Row-Oriented DBMSs

Row-Oriented Data Layout

Row-oriented database management systems store data in records or rows.

- The approach works well for cases where several fields constitute the record, uniquely identified by a key

- Data on a persistent medium, such as a disk, is stored in blocks, so accessing an entire row of information is relatively easy.

- Hence, accessing all of the data from a single column is a lot more expensive

Column-Oriented Data Layout

Column-oriented database management systems partition data vertically instead of storing it in rows

- values for the same column are stored contiguously on the disk

- Storing values for different columns in separate files or file segments allows efficient queries by column

- a good fit for analytical workloads that compute aggregates, finding trends, computing average values, etc

- In order to have a representation of which field is associated with which set of fields, each value will have to hold a key

- Increases the amount of data that is stored.

Distinctions and Optimizations

Reading multiple values for the same column in one run significantly improves cache utilization and computational efficiency. On modern CPUs, vectorized instructions can be used to process multiple data points with a simple CPU instruction

The end-all, be-all is that whether you use a column-oriented or row-oriented store, you need to understand your access patterns. If the read data is consumed in records where most or all of the columns are requested, then you will benefit from a row-oriented approach. Otherwise, you might want to use the column approach.

Wide Column Stores

Wide column stores represent data as a multidimensional map: columns are grouped into column families, and within each family, data is stored row-wise.

Data Files and Index Files

Instead of relying on the OS’s general-purpose file formats, DBMSs store data using implementation-specific storage layouts to optimize for database workloads. This is mainly for:

- Storage efficiency (compact representations, less overhead)

- Access efficiency (fewer I/Os, predictable reads)

- Update efficiency (fast inserts/updates, controlled fragmentation)

Database data is organized into tables. Conceptually, a table is a collection of records (rows), and each record contains multiple fields (columns). In many systems, each table is stored in its own set of files. To retrieve a particular record, the DBMS typically uses a search key (e.g., a primary key or an indexed attribute). Rather than scanning the entire table each time, it relies on indexes—auxiliary data structures that map from key values to the location of the corresponding records.

Most DBMSs separate storage into data files and index files:

- Data files store the actual table records (the rows and their field values).

- Index files store metadata that helps the DBMS find records quickly (e.g., key → record location mappings).

Pages

Both data and index files are divided into fixed-size chunks called pages (also called blocks). Pages are the unit of:

- disk I/O (read/write a page at a time)

- buffering/caching in memory A page is typically the size of a disk block or a small multiple of it (commonly a few KB).

Inserts, Updates, and Deletes

At the storage level, changes to records are often tracked as (key, value) updates where the “value” may represent a full record, a delta, or a pointer to the latest version depending on the design.

In many modern storage engines—especially log-structured ones—records are not immediately overwritten or physically removed:

- Updates may be written as new versions of a record (append-only), and the old version remains until later cleanup.

- Deletes are often represented as a special marker (a tombstone) indicating the record was deleted at a particular time.

- A background process (e.g., compaction/garbage collection) eventually reclaims space from old versions and tombstones.

Data Files

Linked Map of Contexts